FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

05/03/21

Contact: Meaghan Walsh Gerard

Communications and Administrative Director

meaghan@ogeecheeriverkeeper.org

OGEECHEE RIVERKEEPER, CITY OF SAVANNAH LEAD VERNON RIVER RESTORATION PROJECT

Ogeechee Riverkeeper (ORK) and the City of Savannah are partnering to lead a long term project to protect the water quality and ecology of the Vernon River. The Vernon River receives a significant amount of the stormwater leaving the City of Savannah, via Wilshire Canal, Harmon Canal, Casey Canal, and Hayners Creek, all part of the Ogeechee River watershed. The goal is to improve water quality, restore ecological habitat, and “Protect The Vernon River” from current and future threats.

The canals and tributaries that feed the Vernon River are highly impacted by urban development. When stormwater runs across parking lots, through streets, and off of other impervious surfaces it doesn’t have a chance to be filtered through soils before reaching the marsh. This, along with aging sewage infrastructure, failing septic systems, and disconnected riparian habitats, has negatively impacted the canals and creeks of the Vernon watershed.

In 2001 a group of citizens came together to focus on protecting the Vernon River from urban pollution when it was listed as ‘impaired’ by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GA EPD). This allowed ORK and the City of Savannah to apply for grant funding and conduct further testing to trace causes and share the results. In 2012 the committee expanded to a group of stakeholders to create a Watershed Management Plan (WSMP). The plan was released in 2013 and a number of recommendations have been enacted.

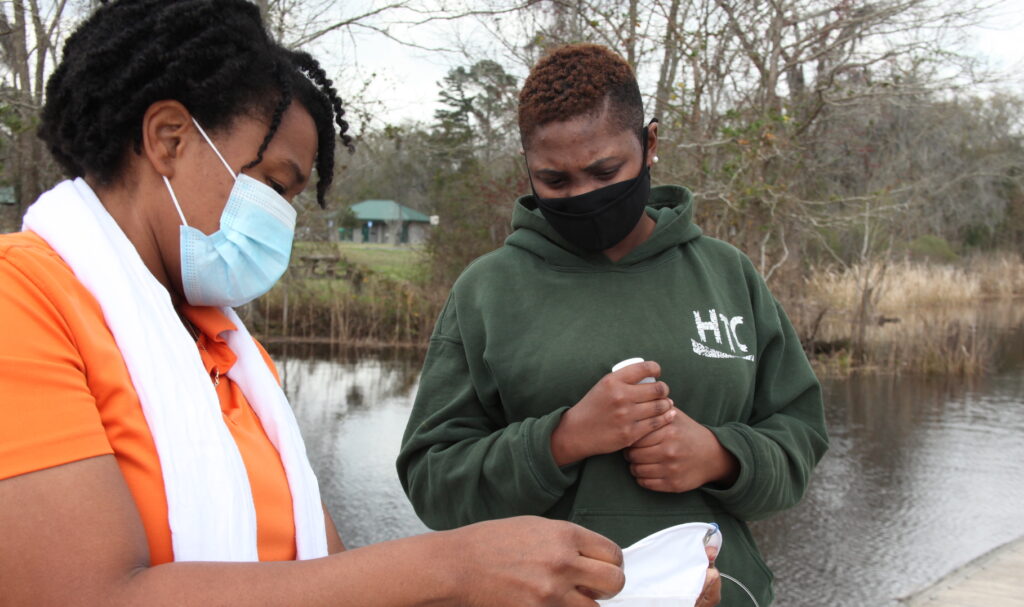

This year, Ogeechee Riverkeeper, the City of Savannah, and other stakeholders are updating the WSMP with new data and recommendations with the goals to: restore the waterways in the Vernon River basin to the point that it can be delisted as an impaired waterbody by GA EPD; and to reduce the amount of litter and plastic pollution entering the waterways.

“All of Savannah’s stormwater infrastructure flows into a public waterway,” says Laura Walker, Water Resources Environmental Manager for the City of Savannah. “These waterways are lifelines to Savannah’s environmental and economic health. We work hard every day to try and keep them fishable and swimmable. But we need everyone to treat the storm system with care. We need everyone to protect the storm drains, ditches, and creeks and keep them clean.”

The steering committee includes representatives from:

- The City of Savannah

- Cuddybum Hydrology

- Ogeechee Riverkeeper

- Savannah State University

- Skidaway Institute of Oceanography (UGA)

- Town of Vernonburg

- Concerned residents from neighborhoods throughout the watershed

“With its gorgeous views and vibrant wildlife, the Vernon River exemplifies why our coastal rivers are such jewels and worthy of our protection,” says Damon Mullis, Ogeechee Riverkeeper and Executive Director. “We are so grateful for the broad group of stakeholders working with us to minimize the threats that urban runoff, and litter and plastic pollution pose to this special waterbody. Local residents are encouraged to volunteer for litter cleanups, citizen science programs, educational events, and more in the coming months.”

Sign up to volunteer, view data, and read the 2013 WSMP at: https://www.ogeecheeriverkeeper.org/vernon

About Ogeechee Riverkeeper: Ogeechee Riverkeeper 501(c)(3) works to protect, preserve, and improve the water quality of the Ogeechee River basin, which includes all of the streams flowing out to Ossabaw Sound and St. Catherine’s Sound. At 402 miles long, the Ogeechee-Canoochee River system drains more than 5,500 square miles of land across 22 Georgia counties. ogeecheeriverkeeper.org